August 14, 2018, Paradise WA

“The Mountain”

In summer 2018 I signed up for a guided mountaineering seminar on Mount Rainier, in the gorgeous Cascade Range. Four years earlier I visited a friend getting her Ph.D. from UW in nearby Seattle. It was my first time in the gorgeous Pacific Northwest. While roaming around town, I caught my first glance of Rainier, towering over the landscape. It was unlike any mountain I had seen before, clearly taller and more isolated than anything in the Rockies, let alone the Northeast. I asked my friend if we could hike it. She looked at me like I had three heads and said “What?! No! You need to like, train for that. And acclimate. It’s like a real mountain.” I decided then and there that the next time I was in Washington, I was climbing Mount Rainier.

Four years later, I had returned to do exactly that. There were a couple of marathons under my belt, along with a dozen or so Adirondack High Peaks. In the months leading up to the climb, I loaded up my 50-liter pack with water and cases of beer and hiked up and down the Hudson Highlands (the closest mountains to NYC). When that wasn’t heavy enough, I added metal weights. The goal was to grow comfortable lugging 50 lbs of weight a couple of thousand feet to basecamp.

You don’t need to be crazy (or spend crazy) to enjoy Rainier national park

Before going any further I should note that Rainier National Park can be thoroughly enjoyed without a hardcore training regimen, or dropping serious cash, or risking life and death on a crevasse-riddled glacier. Here are a few other ways to enjoy America’s most prominent stratovolcano:

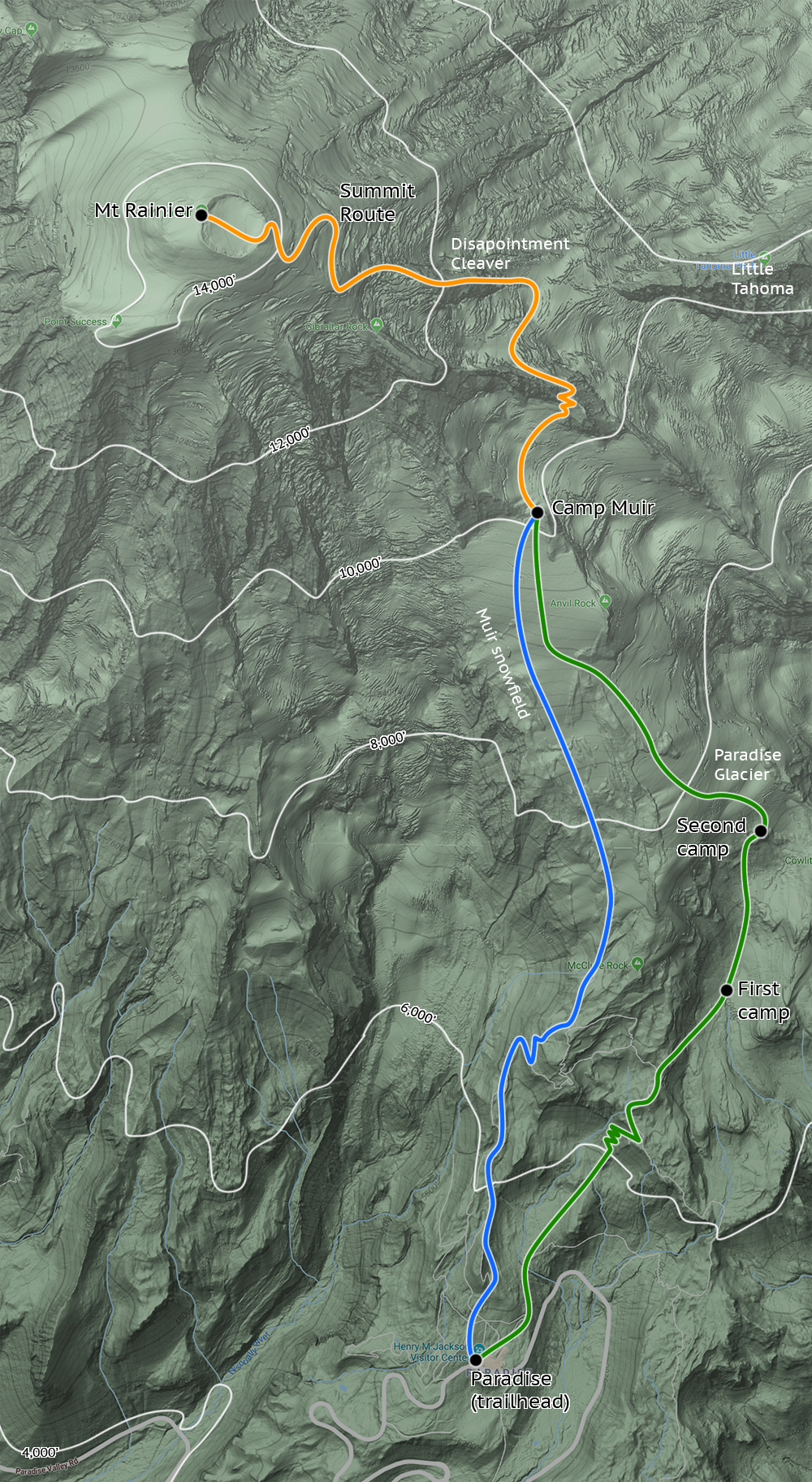

- Paradise to Panorama Point: Paradise is the main point of departure for hikes on the mountain. It’s a mile above sea level and gets some of the most intense snowfall of anywhere on the planet. This means gorgeous wildflowers well into late summer (the photos in this post are from a dry mid-August). You can hike to Panorama Point, climbing over 1000 vertical feet with a round trip distances of roughly 4 miles. [details]

- The Muir Snowfield: Okay, so you want to do something a bit more hardcore than flowers and marmots. And you want to experience snow in summer. The Muir Snowfield will bring you to 10,000′ above sea level, with more than half the trip on snow. It’s not a glacier, which means you don’t need to worry about crevasses or other hazards. If you do spend time on the snowfield, make sure to bring sunglasses (ideally glacier goggles) and plenty of water. [details]

- Elsewhere in Rainier National Park: There are other major visitor centers and hundreds of miles of trails in the park. The Wonderland Trail circles around Rainier at a comfortable distance, providing a many-day backpack that folks rave about.. While I haven’t experienced any of these hikes, I did do a short day-hike just outside the park at High Rock, which I can highly recommend.

Heading above treeline

Our team began our ascent early on a Tuesday morning, from the parking lot in Paradise. The first few miles and 1500 vertical were through the part of the park that most visitors experience. We passed gorgeous meadows of wildflowers and whistling marmots that lend Paradise its well-deserved name. The marked trails were made of well-packed dirt and gravel and clearly featured a lot of excellent trail work that comes with being in a highly trafficked, flagship national park.

Early in the morning, on this sunny day, there were dozens of marmots bumbling about in these fields. And I was basically smitten.

Our team was three guides and nine clients, and we had spent the previous day in Ashford WA, learning all sorts of mountaineering techniques, including various knots and hitches, basic safety protocols, and an overview of the days ahead. Over the next couple of days, we would set up camp progressively higher on the mountain, practicing self-arrest and climbing techniques, “camp craft” and other cornerstones of safe travels on glaciated peaks.

Onto the Paradise Glacier

Around 7000′ we left marked trails and entered the alpine. Soon after we reached the Paradise Glacier. From this point on there were no trees, grass, animals or insects. Just a lot of rock, ice and snow. Rainier is the most heavily glaciated peak in the lower 48, with glaciers said to be 600+ feet thick. You can measure this because glaciers are invisible to radar, something WWII pilots discovered the hard way. All that said, these massive rivers of ice have been in retreat for decades. They now terminate thousands of feet higher up the mountain than they did in old photographs.

We set up the first of three camps, digging out a flat platform for the heavy-duty winter tents we’d be sleeping in. We drank water unfiltered from the glacier’s runoff (no animals) and boiled water to rehydrate dinners.

Training on the Mountain

The next day we practiced building snow anchors and doing crevasse rescue. While traveling on a glacier, there’s always the risk that the “ground” beneath your feet could give out to reveal a massive crevasse. The crevasses on Rainier can be hundreds of feet deep, so this can effectively be like falling off a 10- or 20-story building. For this reason, you travel roped to multiple other people, wearing crampons and holding ice axes at the ready. Should a snow bridge collapse, your teammates are hopefully ready to dig in their tines, anchor you in place, and then set about building a snow anchor and makeshift pulley system to pull you up to safety. You should never travel on a large glacier without the right equipment and teammates or guides experienced in such a rescue plan.

After three nights on the paradise glacier, we traveled over onto the Muir Snowfield, and continued to a final night at Camp Muir, at 10,000 feet. Camp Muir via the Muir Snowfield is safely reached by anyone willing to hike 5000 feet from the parking lot (see bullets above). It had several luxuries we had gone without the past few days, including permanent structures and toilets. There’s a public bunkhouse that anyone can use for an overnight, and a ranger station.

Taking care of business

Taking care of business on a glacier is … interesting business. Because the mountain is more or less devoid of an ecosystem, there are no bacteria nor flora and fauna to return your morning glory to the good earth. In other words, the scat you produce stays frozen in place for an unfortunately long time. To deal with this, we had to place all #2s in blue baggies that we then kept in our packs (ideally a separate compartment). Finally, having reached Camp Muir we could dispose of these in containers that are flown out by helicopter each day.

That afternoon we synced up with another climbing group doing a much shorter, two-day ascent. After some Q&A related to summit day, we ate dinner and hit the sack around 4 or 5 in the afternoon … which sounds early, but I was out cold in about an hour.

Summit Day

Summit “day” began around 11 pm when we were awoken via headlamp by the head guide. It was a quick scramble to get dressed and eat breakfast. By midnight we began our ascent to the summit.

An “alpine start” takes place in the wee hours of the morning or even the night before for safety reasons. The sun (and warm temperatures in summer) thaw the upper mountain by midday, making snow bridges unstable and dangerous to walk across. The same forces make ice falls and rockfalls more likely to release hazards onto hikers. Finally, as we’d discover at the summit, the temperature can swing wildly at high altitude.

The ascent began under a gorgeous clear sky full of stars. Roped in and concentrated on maintaining safe spacing between my teammates, I was unable to capture many excellent photos of this. But the night was stunning. We began by crossing a small glacier between Camp Muir and Cathedral gap, a small cleaver with a switch back to 11,000 feet. Here we took our first break, drinking water and eating snacks.

Mount Rainier has real glaciers!

We then crossed a larger and more rugged glacier where I caught my first glimpses of the large, upper-mountain crevasses. A glacier moves downhill, perhaps inches a day, like a slow-motion river of ice. As it travels over a ridgeline onto a steeper slope, it deforms and cracks, forming crevasses. Crevasses can widen and narrow as the river undulates down the mountain.

Soon we had come to Disappointment Cleaver, a prominent rocky ridge that “cleaves” the summit glaciers apart. In late summer, the cleaver was bare, volcanic rock. We began up the endless switchbacks of the cleaver, which rose more than a thousand vertical feet in less than a half mile—steep to say the least! Still roped in and wearing crampons, to save time, I saw sparks fly through the dark night as tines made contact with soft, dry, volcanic rock.

The volcanic rock was very different than anything I’d experienced hiking in the northeast. It was soft and chalky and crumbled easily. The path ahead was full of small bits of scree and gravel. Occasionally rocks would tumble down the route, which meant we all had to be quite vigilant for the folks behind us.

The Final Push to Mount Rainier’s Summit

Gaining the cleaver placed us back on soft, quiet snow and just under 13,000 feet above sea-level (more than two-thirds of the way from Camp Muir to the summit by vertical). The upper mountain was steep and we ascended the glacier via long, circuitous switchbacks. The route occasionally crossed narrow (but deep!) crevasses, where the guides of days prior had laid down aluminum ladders and fixed ropes. Walking across a standard Home Depot ladder while glancing down into a crevasse 100+ feet deep was certainly a hair-raising experience.

The journey was growing more exhausting. Being roped together meant traveling at a fixed pace, in a very disciplined fashion. We went at roughly 1000 vertical feet per hour with a break between each. One of the hardest tasks for me was maintaining the proper distance between myself at the teammate in front of me, particularly when rounding switchbacks. And the altitude was starting to make itself known.

While 14,000 feet is high enough to “experience altitude”, I’ve been told it’s not high enough to bring about acute medical issues (at least for short trips). Between this trip and skiing in the Rockies, I can happily report the worst I’ve experienced is some shortness of breath and fatigue. I once had a massive headache at Breckenridge in Colorado, but I think that had more to do with being on snow without goggles or sunglasses than the altitude.

The Summit Crater

The sun slowly rose above the horizon as we reached the uppermost portions of the stratovolcano. The slope began to level off and soon we had reached the rim of the summit crater. The crater rim is bare rock, and quite warm to the touch: a reminder that Rainier is an active volcano! A small glacier fills the summit crater. I’ve read that this glacier is riddled with tunnels and pools of water and provides shelter in an emergency.

We unroped to travel across the crater, with Columbia Crest (the true summit) waiting at the far end. There we paused for photos and a brief summit celebration. There wasn’t a trace of wind in the air, nor a cloud in the sky. But the temperature began to climb.

The descent

Eventually, we re-roped and said goodbye to the summit crater. We climbed over the rim and began our descent. Almost immediately the baking sun seemed to heat the whole mountaintop to 80+ degrees Fahrenheit, and I was suddenly very thankful I did not wear long underwear. The night before, the senior guide from the other group had recommended wearing long underwear. The junior guides later told us that it was an absolutely terrible idea. I was very glad I listened to the latter group.

Descending in the broad light of day, I came to realize just how harrowing the high break in the mountain was. The dark crevasses and steep slopes were now fully illuminated and scarier than before. The view was also stunning in new ways.

We descended to the cleaver, and the rocky descent was sheer murder on my toes. The leather mountaineering boots I had rented were slightly large, and my toes slipped back and forth in my wet wool socks, slowly removing more than a couple layers of skin.

Back to Paradise

Eventually, we made it back to Camp Muir. We packed up all the camping gear and began our descent, the same day to Paradise. This time we traveled entirely along the Muir snowfield, sliding down the peaks of sun cups until reaching the meadows. It was a long summit day, 4000 feet up, and 9000 feet down. The final stretch was through the visitor trails, which on this Saturday afternoon were packed with folks in t-shirts and shorts. We must have looked fairly ridiculous in 100-liter packs with ice axes sticking up the backside. But it was worth it for the amazing experience on Mount Rainier.